by John Doan, published originally in the September 1988 issue of Frets magazine

Until recently, harp guitars usually graced the back walls of pawn shops and junk stores, or played the ignoble role of mascot in the old guitar emporium downtown. Collectors of the offbeat and curious kept them piled in instrument mausoleums, or hung like stuffed spearfish over the home entertainment center, but no more. Today many guitarists are experimenting with different tunings and custom-designed instruments–often with additional bass or treble strings. The harp guitar may be an instrument whose time has come again.

Until recently, harp guitars usually graced the back walls of pawn shops and junk stores, or played the ignoble role of mascot in the old guitar emporium downtown. Collectors of the offbeat and curious kept them piled in instrument mausoleums, or hung like stuffed spearfish over the home entertainment center, but no more. Today many guitarists are experimenting with different tunings and custom-designed instruments–often with additional bass or treble strings. The harp guitar may be an instrument whose time has come again.

Predecessors to the Harp Guitar

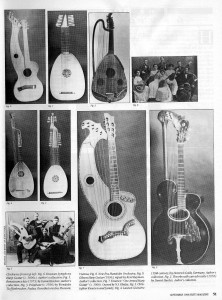

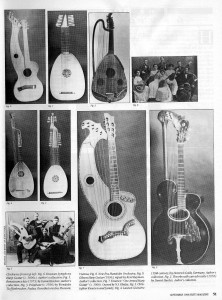

Our interest in instruments with many strings is not without precedent. During the Renaissance (1400-1600), the new polyphonic musical style gave a privileged role to all instruments capable of producing several notes at once. String instruments developed during this period included the mandora, bandora, orpharion, penorcon, stump, cittern, and lute. The guitar at that time had four pairs of strings, and was used primarily to accompany singing. It would be some 200 years before it would evolve to approximate what we call the guitar today, with its characteristic six single strings and EADGBE tuning. The lute, however, had already acquired five pairs of strings (each pair of strings known as a course) by the 1400s, six courses by the 1500s, and, by the end of the century, seven- and eight-course instruments were common.

Our interest in instruments with many strings is not without precedent. During the Renaissance (1400-1600), the new polyphonic musical style gave a privileged role to all instruments capable of producing several notes at once. String instruments developed during this period included the mandora, bandora, orpharion, penorcon, stump, cittern, and lute. The guitar at that time had four pairs of strings, and was used primarily to accompany singing. It would be some 200 years before it would evolve to approximate what we call the guitar today, with its characteristic six single strings and EADGBE tuning. The lute, however, had already acquired five pairs of strings (each pair of strings known as a course) by the 1400s, six courses by the 1500s, and, by the end of the century, seven- and eight-course instruments were common.

As the Renaissance gave way to the Baroque (1600-1750), lutenists strove to keep pace with the new developments in music. They composed more and more pieces in alternate tunings, lowering basses (bass strings), and ultimately adding more strings to increase the range and flexibility of the instrument. The problem they confronted was the limited reach of the left-hand fingers to stop the strings. There was only so far that the width of the fingerboard could be extended. And in order to get a good tone in the lower register, the strings needed to be longer. Continue reading →