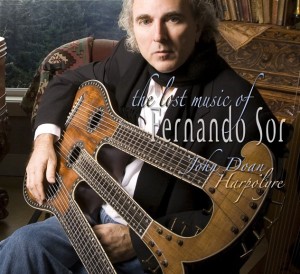

Fernando Sor, known as “The Father of the Classical Guitar”, wrote very lyric and disarmingly beautiful music in 1830 for a three necked, 21-string guitar called the harpolyre. It has gone unplayed until now and I am hoping that you would like to be involved in the discovery of this exciting music by either acquiring a CD or coming out to an upcoming concert. With this recording I hope to give attention to an important forerunner of the harp guitar and to bring back to life some incredible music that went beyond six strings long ago.

Listen to The Lost Music of Fernando Sor

- 1. Six Petite Pieces Progessives – Andante 2:04

- 2. Six Petite Pieces Progressives – Andantino 1:31

- 3. Six Petite Pieces Progressives – Andante 3:25

- 4. Six Petite Pieces Progressives – Cantabile 2:21

- 5. Six Petite Pieces Progressives – Andante 4:36

- 6. Six Petite Pieces Progressives – Moderato 3:13

- Marche Funebre 8:55

- 1. Trois Pieces Pour La Harpolyre – Andante Largo 5:43

- 2. Trois Pieces Pour La Harpolyre – Andante Cantabile 5:33

- 3. Trois Pieces Pour La Harpolyre – Andantino 7:39

total Time 45:00

The Lost Music of Fernando Sor (Liner Notes)

The harpolyre, and the music composed for it, came about as the “classical” age of reason was giving way to the “romantic” era when feeling and intuition were to be the guide to insight and enlightenment. The lyre of the ancient Greeks had been revived in the 1780’s as the lyre-guitar in France proudly displaying a balance of beauty and function with its three bass strings and three treble strings allowing two full octaves to be played within one position. It initially took it’s music from the five-course guitar that was popular at the time, then the same music appeared in print for either instrument, and by the early 1800’s the standard of six-strings for both the lyre-guitar and the guitar became the norm. In this way the lyre-guitar did much to popularize the six-string guitar that had evolved out of a five-course instrument (a point overlooked by many contemporary guitar historians and players). By the late 1820’s solo classical guitarists who had been accustomed to performing within the intimacy of small parlor settings found themselves thrust before the public in larger rooms calling for louder, fuller, and more resonant instruments that had yet to be invented. By this time the lyre had become the very symbol for music and in the spirit of preserving and extending the basic design of the lyre-guitar and perfecting various aspects of the classical six-string guitar the harpolyre was born.

In 1828 the famous music critic F. J. Fetis wrote in the Revue Musicale a concert review of Fernando Sor (1778-1839) who performed on a six-string guitar at the end of an evening that featured a succession of brilliant soloists on instruments other than guitar that included none other than the famed Franz Liszt at the piano. Although Sor’s music was acknowledged as “pure” and possessing “elegant harmony”… Fetis went on to say,”… we regretted that the sound of the instrument was not fuller. M. Sor seems to us to have neglected too much this essential aspect of an instrument which in itself is not sonorous enough.” This sadly was a complaint in various reviews of Sor’s performances at this time, and no doubt was applied to other guitarists as well. (B. Jeffery pg. 100 2nd ed.)

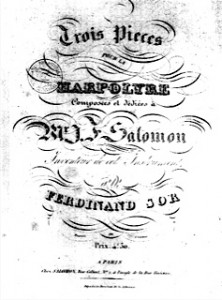

In 1829 a French guitarist/inventor J. F. Salomon approached Sor, as well as other prominent guitarists of the day, with his invention of the harpolyre with three necks, and twenty-one strings, promoting what he saw as numerous advantages over the six-string guitar. There was so much excitement about the possibilities of the harpolyre that in 1830 The Revue Musicale printed a report by a prominent Arts committee, recommending that Mr. Salomon be publicly given a medal for inventing the instrument. (B. Jeffery pg 98 2nd ed.). It was at this time that Sor’s interest in the harpolyre resulted in the series of pieces that are found on this recording.

In 1829 a French guitarist/inventor J. F. Salomon approached Sor, as well as other prominent guitarists of the day, with his invention of the harpolyre with three necks, and twenty-one strings, promoting what he saw as numerous advantages over the six-string guitar. There was so much excitement about the possibilities of the harpolyre that in 1830 The Revue Musicale printed a report by a prominent Arts committee, recommending that Mr. Salomon be publicly given a medal for inventing the instrument. (B. Jeffery pg 98 2nd ed.). It was at this time that Sor’s interest in the harpolyre resulted in the series of pieces that are found on this recording.

Sor wrote these pieces in Paris in 1830 and had them published by Salomon who in 1831 discontinued his harpolyre business, returned to his home town of Besançon, France, and by one account was greatly depressed by the failure of his enterprise and died soon afterward. Apparently all hope and promise of the instrument and its music died with Salomon and it eventually fell into disuse. By 1840 the popularity of the six-string guitar also began to pass as guitars with one to twelve additional bass strings began to gain in popularity, a trend that lasted for some eighty years. In light of this progression one could see the harpolyre as a forerunner of this trend of adding strings to the guitar to expand it’s range, resonance, and capabilities.

In examining the instrument one is first impressed with its three necks leading many today to wonder if one needed as many arms to play such a thing! Its logic begins with the central neck identical to the six-string guitar. The seven strings on the Chromatic neck to the left (as looking straight on) descend by half steps starting with Eb (just below the guitar’s sixth string E) to A an octave below the guitar’s fifth string A adding to the guitars lower range. The additional Diatonic neck to the other side of the central neck is comprised of eight strings ascending from C (3rd fret, 5th string) up an octave like white keys of the piano. On this neck many harp-like effects are made that expand tonal color along with an opportunity to distribute the work of the left and right hands to play the instrument. The additional strings on both sides of the guitar neck add resonance to the entire instrument and through the plucking of bass notes with the right hand thumb the left hand moves more freely without having to hold down a bass note on the guitar neck while playing melodies and harmonies. The design of the harpolyre also allows for easy access to the fingerboard’s highest positions well beyond the 12th fret. Salomon in his method book adds,”Beside the fact that it makes more superior sounds in intensity and quality its elegant shape makes it susceptible to figure in with great advantage to the ornaments of a living room.” Basically, and I know this from experience, it takes one’s breath away when you enter the room where it is displayed. These were the features, along with a larger body and greater volume that were thought to “perfect” the guitar.

In examining the instrument one is first impressed with its three necks leading many today to wonder if one needed as many arms to play such a thing! Its logic begins with the central neck identical to the six-string guitar. The seven strings on the Chromatic neck to the left (as looking straight on) descend by half steps starting with Eb (just below the guitar’s sixth string E) to A an octave below the guitar’s fifth string A adding to the guitars lower range. The additional Diatonic neck to the other side of the central neck is comprised of eight strings ascending from C (3rd fret, 5th string) up an octave like white keys of the piano. On this neck many harp-like effects are made that expand tonal color along with an opportunity to distribute the work of the left and right hands to play the instrument. The additional strings on both sides of the guitar neck add resonance to the entire instrument and through the plucking of bass notes with the right hand thumb the left hand moves more freely without having to hold down a bass note on the guitar neck while playing melodies and harmonies. The design of the harpolyre also allows for easy access to the fingerboard’s highest positions well beyond the 12th fret. Salomon in his method book adds,”Beside the fact that it makes more superior sounds in intensity and quality its elegant shape makes it susceptible to figure in with great advantage to the ornaments of a living room.” Basically, and I know this from experience, it takes one’s breath away when you enter the room where it is displayed. These were the features, along with a larger body and greater volume that were thought to “perfect” the guitar.

In the late 1800’s, during a period of great nationalism, various Spanish guitarists, most prominently Francisco Tarrega, promoted the playing of the traditional six-string “Spanish” guitar. This was greatly aided by the innovative construction designs of Antonio de Torres that improved the instrument’s dynamics, and tonal qualities.

By the mid-twentieth century Andres Segovia and his followers, while promoting the virtues of the six-string guitar in order to legitimize a school of guitar playing found themselves publicly opposed to other forms of guitar. Segovia writes in the Guitar Review (#39, Summer 1974),”I absolutely do not believe that the guitar requires additional strings, neither at the right nor at the left of the fingerboard. The six it traditionally possesses are quite sufficient.”

He goes on to say that by simply using a few altered tunings this “saves the guitar from the peril of additional strings which would destroy the equilibrium now existing between its basses and it trebles.” Perhaps instead of limiting one’s prospective to how six strings are “good” and more strings are “bad” the broader position would be to ask why thousands of musicians for hundreds of years used additional strings on their lutes and guitars and how did that influence their playing and composing for such instruments?I believe that because of this bias against guitars that did not resemble the “Spanish” six-string guitar, instruments like the harpolyre, not to mention the bass-guitar, the Schrammel guitar, the harp guitar, harp-lute guitars, and lyre guitars, etc, have hardly received notice by guitar historians and players alike in the last fifty years. Segovia finalizes his earlier point by stating “Remember also that Sor … did not feel a need for additional strings…”

It is here I leave you with the truth of the matter as you listen to this most delightful collection of disarmingly passionate and eminently sing-able music Fernando Sor wrote for the 21-string harpolyre. Sor’s leading biographer, Dr. Brian Jeffrey states that Sor was,”a man who had spent his life in music as a whole and not merely in the limited corner of it that is the guitar.” (Pg 96, 2nd ed.). Sor says in his method published the same year as his harpolyre music “”I Love music, I feel it.” Perhaps that is all that matters.

Thanks and Appreciation

Guitar History Consultants:

Dr. Ron Purcell for his continued teaching and inspiration from my days studying with him at California State University at Northridge (1970-74) to the present.

James Westbrook of the Guitar Museum of Brighton, England for his great passion and detailed insights into early guitar history.

Dr. Brian Jeffrey for his significant biography “Fernando Sor – Composer and Guitarist, Tecla, London, England, 1977 and 1994. From this work I became aware of Sor’s music for the harpolyre.. I also thank him for his friendship and openness to discuss in person the life and times of Fernando Sor.

Gregg Miner of the Miner Museum of Los Angeles, California, and editor of www.harpguitars.net for his valuable consultation, encouragement and friendship in all things harp guitar.

Lyre Guitar Research:Alain Bieber for his scholarship on the lyre-guitar, informative correspondence, and his friendship in meeting in his home in Paris, France.

Eleonora Vulpiani for her accomplished performing on the lyre-guitar, correspondence, and fine work “Lira-Chitarra – Etoile charmante, tra il XVIII e il XIX secolo, self published, Rome, Italy 2007.

Stephen Bonner for his excellent work “The Classic Image: European History and Manufacture of the lyre guitar, 850-1840, Bois de Boulogne, Harlow, Essex, England 1972

Library Assistance: Bibliotech Nationale, Paris, France for providing the microfilm of Sor’s harpolyre works and a copy of Salomon’s harpolyre method.

Doreen Simonsen – Humanities and Fine Arts Librarian – Willamette University for her expert assistance in securing Salomon’s method along with additional supporting documents.

Harpolyre restoration:

Martin Bowers of Essex, England (1979)

Kerry Char, Jeffrey Elliott (2006)

Curtis Daily of Aquila Strings – www.aquilausa.com of Portland, Oregon.

Assistance to acquire the harpolyre:

Benoît Meulle-Stef of Brussels, Belgium

Stephen Sedgwick of Kent, England

Karla Fisher and Brent Bunker of Oregon

Rainer Krause of Berlin, Germany a noted instrument collector who sought out and acquired the harpolyre heard on this recording so that I could fulfill a thirty year vision of performing and recording Sor’s lost music.

French to English translations of Salomon’s Method: Christian Selleron

Recording Engineer: The one and only C. J. Washington

Editing, Mixing, and Mastering: Harald Peterstorfer of Recordingart, Austria

Cover Photo: Frank Miller

Technical, Graphic, and all around support: Deirdra Doan

You must be logged in to view this content.