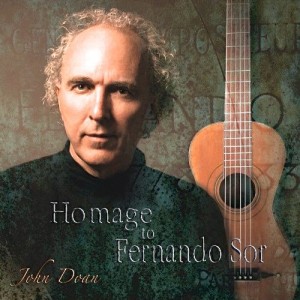

Homage to Fernando Sor is John Doan’s newest release. It pays tribute to the ground-breaking work by Fernando Sor, the father of the modern guitar. John explored the powerful, influential work of Fernando Sor in his album, “The Lost Music of Fernando Sor.” He takes the passion of Sor further by exploring the legacy of the music of Fernando Sor and what the his work would sound like today if Sor had the strong rich heritage of disciples continuing his theories and philosophies into the future. Even today, Sor’s work continues to be required studies for the classical guitarist.

John Doan Reflects on Writing “Homage to Sor”

I have always enjoyed playing Sor’s music and was especially intrigued by the adventure of discovering his forgotten works for harpolyre that I have since recorded and transcribed for the guitar. Playing that music on an original instrument from 1829 added a certain nostalgia and romance to the experience that subsequently opened me up to find and appreciate an early 19th century six string guitar by the Panormo family. It may be the very instrument that Sor commissioned from them in 1819. This thought has added greatly to my awe and fascination for Sor by being able to touch and play the very instruments that were part of his world. His music and this incredible instrument along with some of my personal identification with he and his times have served as an inspiration to this collection of pieces written in Homage to Sor.

Once I got the Panormo home from repairs and strung it up I was instantly struck by its full and surprisingly rich tone for such a small instrument. Where has it been all these years? Did Sor try it out after the Panormos completed it? Is this the guitar that Julian Bream made his first public performance on after his father was forced to sell his beloved Macaferri harp guitar to satisfy the harp guitar’s censorship by the president of the London Guitar Society?

Once I got the Panormo home from repairs and strung it up I was instantly struck by its full and surprisingly rich tone for such a small instrument. Where has it been all these years? Did Sor try it out after the Panormos completed it? Is this the guitar that Julian Bream made his first public performance on after his father was forced to sell his beloved Macaferri harp guitar to satisfy the harp guitar’s censorship by the president of the London Guitar Society?

Every note I played on it was beautiful, captivating and inspiring. By 2 o’clock in the morning my wife interrupted by waking dream urging me to come to bed by saying that it will still be there in the morning. I had the most pleasant sleep in those early morning hours. I awoke with a smile having heard the tone of the instrument within my dreams. There was so much music I heard and I realized that I had never heard any of it before. I ran to sing it into my recorder and feverishly wrote as much of it down as I could before it faded from my memory. I did not know then that this music was the first of a collection I would imagine within a continuum of time between Sor’s era and our own.

The instrument, if it knows anything, it knows nothing of the 21st century that we live in today as it is apparently frozen within it’s hand crafted shape and nineteenth century woods and sensibilities. It appears steadfast to its design and purpose of being a window to some ascendant experience of music back when music was to be mused about and not just for us to be amused by in seeking a moment of passing entertainment. This was very much Sor’s dilemma of living during a time that both democratized music as well as opened the door to virtuosos and want-a-be performers to busy their fingers over fingerboards in an effort to dazzle an undiscriminating audience.

The instrument, if it knows anything, it knows nothing of the 21st century that we live in today as it is apparently frozen within it’s hand crafted shape and nineteenth century woods and sensibilities. It appears steadfast to its design and purpose of being a window to some ascendant experience of music back when music was to be mused about and not just for us to be amused by in seeking a moment of passing entertainment. This was very much Sor’s dilemma of living during a time that both democratized music as well as opened the door to virtuosos and want-a-be performers to busy their fingers over fingerboards in an effort to dazzle an undiscriminating audience.

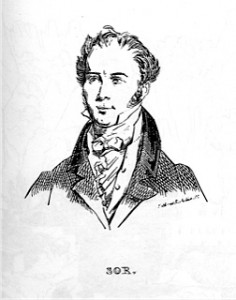

Sor’s following the muse first and the guitar second is something I really love him for and aspire toward in my writing. Thinking musically is the key. Thinking idiomatically for the guitar indeed renders sound and a “music” of sort but it tends to lean toward being a by product of the physical engagement of playing the instrument than something based on musical language and thinking. I wonder if composers of the more idiomatic music for the instrument can sing what they play? I believe this was a model that Sor used. I challenge my students to sing what they play and it often is the beginning of profound change in the approach they take to their music making. It seems so simple: thinking musically leads to playing musically.

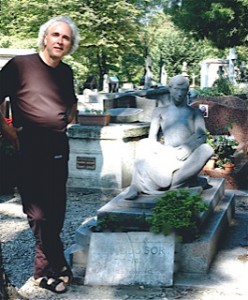

I read and reread Dr. Brian Jeffrey’s biography of Sor and poured over Sor’s 1828 “Method for the Spanish Guitar” to understand Sor the composer and the man better. Dr. Jeffrey generously met me in London one summer’s day and guided me to the very addresses Sor lived and performed at during the peak of his career. I then visited Paris and went to the Hotel Favart where Sor first lived, to his later apartment on the Marché Saint Honoré and then graveside were his remains now rest in the Montmartre Cemetery. Pre-eminent Sor scholars Josep Maria Mangado and Josep Dolcet showed me the streets of Barcelona where Sor grew up and later had his early music career and then with them walked the grounds of the Monastery at Montserrat where he lived from ages 11-18 while a member of the famous boys choir.

I read and reread Dr. Brian Jeffrey’s biography of Sor and poured over Sor’s 1828 “Method for the Spanish Guitar” to understand Sor the composer and the man better. Dr. Jeffrey generously met me in London one summer’s day and guided me to the very addresses Sor lived and performed at during the peak of his career. I then visited Paris and went to the Hotel Favart where Sor first lived, to his later apartment on the Marché Saint Honoré and then graveside were his remains now rest in the Montmartre Cemetery. Pre-eminent Sor scholars Josep Maria Mangado and Josep Dolcet showed me the streets of Barcelona where Sor grew up and later had his early music career and then with them walked the grounds of the Monastery at Montserrat where he lived from ages 11-18 while a member of the famous boys choir.

By way of these pilgrimages to sites where Sor lived he was transformed in my mind from a composer from the early nineteenth century into a real person who walked the very streets that I had walked nearly two centuries later. I began to think that he was a real person who breathed the air like us, walked in the sunlight and ate and slept and laughed and cried like us. Sadly, it seems easiest to think that he and all those before us were just here for a period but after their passing away they are no longer with us. All of his humanity with the passage of time somehow becomes reduced to a few letters on a page in a book, remote, distant, and relatively unknowable.

As Sor became more real to me I wondered if each of his pieces might be like a letter placed in a bottle and set out unto the sea of time? As a composer and performer I began to receive his music like messages that had gone unheeded. I began to understand Sor’s musical language as a dynamic of his personality and the challenges he faced in turbulent times. I can only imagine that he lived through struggles, measured some successes and finally had to adjust to growing older and having to accept being productive within a narrower climate of guitar playing leaving his thrilling days of choral, ballet, piano and vocal music behind. I too have had my successes and set backs and like all of us am getting older and so I embarked on answering some of his “musical letters” with some of my own.

As Sor became more real to me I wondered if each of his pieces might be like a letter placed in a bottle and set out unto the sea of time? As a composer and performer I began to receive his music like messages that had gone unheeded. I began to understand Sor’s musical language as a dynamic of his personality and the challenges he faced in turbulent times. I can only imagine that he lived through struggles, measured some successes and finally had to adjust to growing older and having to accept being productive within a narrower climate of guitar playing leaving his thrilling days of choral, ballet, piano and vocal music behind. I too have had my successes and set backs and like all of us am getting older and so I embarked on answering some of his “musical letters” with some of my own.

It is my hope that others will find this music someday and will enjoy its effort to celebrate music and the value we can draw from making a bow to those who have come before us. This music not only pays homage to Fernando Sor but also homage to living life as fully as possible, to wondering about things of beauty, to ponder our own existence, our own vulnerability, our very mortality. Some of the music may seem sad and lonely but it mostly feels to me like a savoring of cherished moments, even while the moments are passing before our eyes as we, our children, our friends, my students grow older. These are like love letters valuing the moments we have, surrendering to each moment as well as to something incredibly greater then we will ever understand.

From winter to spring each of these pieces were like butterflies drifting about in my dreams and imagination. Although I was suppose to be doing other things like my emails, accounting, preparing for teaching or concerts I put those things aside and grabbed my butterfly net and chased after the distant melody, that far away harmonic change, that moment of a waking dream, when I touched something of Fernando Sor and he touched me.

- Homage Em 3:44

- Homage Dm 2:51

- Homage Am 4:49

- Homage Bm 3:46

- Homage D 2:38

- Homage C 2:35

- Homage Am 4:54

- Homage Bm 4:23

- Homage Cm 8:36

- Homage C 4:05

- Homage Am 3:42 Postlude (46:07 total)

You must be logged in to view this content.